Trigger warning: Please note this story contains descriptions of intimate partner violence/domestic violence, which may be distressing for some readers.

If not for her children, an ONA member we’re naming Alice to protect her identity might not be here today.

And all because of a person who was supposed to love her.

“I’ve been a proud registered nurse for 20 years,” she says. “While in the workplace, I was described as strong, confident and an advocate. But behind the doors of my home, I was living the private hell of intimate partner violence [IPV].

“One night last year, my life forever changed. I believed I was going to die at the hands of my spouse had I not had the fight in me and the knowledge that my two children were upstairs sleeping. If I couldn’t protect them, I knew my worst nightmare would happen. He was charged with four counts of assault causing harm, strangulation, assault with a weapon, animal cruelty and three counts of uttering threats to cause death.”

Grim statistics

Tragically, Alice’s story is not unique – far from it.

1/3

of workers in Canada have experienced intimate partner violence

In fact, the country’s first-ever survey on domestic violence in the workplace, Can Work be Safe When Home isn't?, from the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC), which partnered with researchers at the University of Western Ontario, shows that one in three workers in this country have experienced domestic violence at some point in their lives. (Please note the CLC uses the term “domestic violence” while ONA generally says “IPV.”)

The CLC, of which ONA is affiliated through our membership in the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions, defines domestic violence as “any form of physical, sexual, emotional or psychological abuse, including financial control, stalking and harassment that occurs between intimate partners of any gender, who may or may not be married, common law or living together. It can also continue to happen after a relationship has ended.”

“Women experience more serious injuries and are significantly more likely than men to be hospitalized from domestic violence injuries,” says CLC Human Rights Department National Director Vicky Smallman, who presented a half-day education session on this topic at ONA’s recent Biennial Convention.

“They’re twice as likely as men to be sexually assaulted, beaten, choked or threatened with a gun or knife. Indigenous women are five to seven times more likely to be killed. Sixty per cent of women with disabilities and 65 per cent of trans people experience violence, and lesbian, gay and bisexual people might also be at greater risk.”

Shockingly, she adds that one in six women die from domestic violence in Canada every single week. For ONA, that has tragically included members Shannan Hickey, RN, from Belleville who was brutally murdered in May 2024, and Lori Dupont who lost her life in 2005 at the Windsor hospital where her ex-partner also worked.

ONA mourns their loss and honours their lives and the lives of all women impacted by gender-based violence and discrimination, including the 14 women who were murdered at l’École Polytechnique de Montréal in 1989, during National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women, acknowledged on December 6.

We also affirm our unwavering commitment to advocating for a province, country and world free from gender-based violence.

“The shockingly high rates of intimate partner violence and femicide are a longstanding crisis we must act on,” states Provincial President Erin Ariss. “Every statistic represents a person, a family and a future stolen. As nurses, as women, as community members, we all have a responsibility to do more to end intimate partner violence.”

ONA members and other supporters participate in a solemn vigil for our fallen colleague Shannan Hickey.

ONA advocacy

For ONA, that approach has always been multi-faceted.

We made frequent reference to IPV in our recent Code Black and Blue campaign on workplace violence because “the link between intimate partner violence and attacks on health-care workers, who are overwhelmingly women, is crystal clear,” explains Ariss. “Both involve aggression towards women and blaming the victim. And incidents of both are largely underreported and normalized.”

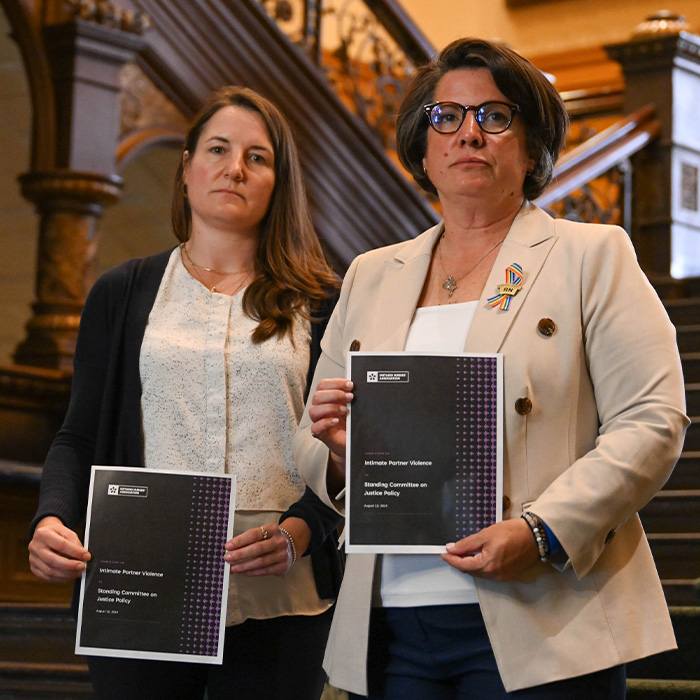

We have also extensively lobbied governments over the years, including speaking in front of the Standing Committee on Justice Policy in August 2024 in support of the Ontario NDP’s Bill 173, Intimate Partner Violence Epidemic Act, 2024 (since retabled as Bill 55, Intimate Partner Violence Epidemic Act, 2025), and providing a formal submission containing 17 recommendations.

Provincial President Erin Ariss (right) and member Michelle Bobala, a forensic nurse and sexual assault nurse examiner, stand on the steps of Queen’s Park in August 2024 holding ONA’s submission on IPV, which they presented to the Standing Committee on Justice’s Policy’s subcommittee studying this topic.

Bill 55 would declare IPV an epidemic, as both Nova Scotia and New Brunswick have done, and form a committee to explore supports for survivors that are desperately needed now. But while it was ordered for second reading this past June, the bill shamefully still hasn’t been passed into law. Instead, after years of delays, the Ford government passed a watered-down motion in the House this fall calling IPV an “endemic,” which ONA doesn’t believe holds the same degree of urgency as epidemic.

However, ONA has had success in this area. We played a pivotal role in the Coroner’s inquest into Dupont’s murder and as a result, Bill 168 incorporated obligations on employers regarding workplace violence and harassment and required these issues be dealt with through an occupational health and safety lens. But the fight continues.

Pointing to this critical achievement, Smallman says political action is just one of the ways unions in Canada have made progress in fighting domestic violence in recent years, adding that collective bargaining language to address issues such as paid leave and workplace safety planning is another.

And that’s important because for people experiencing it, who Smallman says can’t leave their situations for an array of reasons, including a history of abuse, fear of being on their own, economic uncertainty, the belief the abuser can change, an unwillingness to move children and pressures from family/culture norms, time is not on their side.

“Even asking that question blames the woman when it’s not her fault the abuse is happening,” she stresses, noting that newcomers, women in rural communities, racialized and Indigenous women, and trans people also face additional barriers attempting to leave their abusers.

Spills into the workplace

“As nurses and health-care professionals, we’re on the front lines of care for those who have suffered gender-based or intimate partner violence,” notes Ariss. “Not only do we provide care for these patients, but we also witness first-hand the trauma they have suffered. But people experiencing intimate partner violence also work amongst us. It’s not confined to their homes; it spills into their workplaces.”

In fact, CLC survey statistics show that 53.5 per cent of people experiencing domestic violence continue to work, almost 83 per cent of whom say it negatively impacts their work performance. For 8.5 per cent, that has resulted in losing a job due to domestic violence, which is particularly troubling as work can interrupt their isolation through contact with others and allows them space to look up supports away from their abuser. Not being able to make or access their own money also makes them feel significantly more trapped.

More than half of those experiencing IPV reported at least one type of abusive act in or near their workplace.

“Domestic violence impacts work, which means workplaces should be involved,” explains Smallman, noting that more than half of those experiencing it reported at least one type of abusive act in or near their workplace, including threatening phone calls/texts and stalking.

“And it’s not just the person experiencing violence who is affected at work; their co-workers are as well. For those who have left an abusive relationship, their workplace is often the only place where their ex-partners know where to find them.”

In some cases, like Alice’s, they work with their abusers, which can compound an already dire situation.

“Because of what was happening in my home, and the fact that I worked with my abuser and experience trauma because of the nature of my job and a toxic work environment, I developed complex PTSD,” she says, adding that trying to hide what she had been going through for 20 years “so people wouldn’t think I was weak or tell me to leave” also contributed to her diagnosis.

I’m told I should find my happy place. That I don’t need to be scared and should move on.

“So many people don’t know the impact and longstanding changes that occur when you experience intimate partner violence. I’m now ‘safe,’ but in a constant state of anxiety. I always look over my shoulder and jump, shudder or cry if anyone raises their voice. I isolate often. I deal with forever not feeling good enough while trying to handle daily struggles. I smile and advocate strongly for my colleagues as part of the union, but internally I struggle. Yet, I’m told I should find my happy place. That I don’t need to be scared and should move on.”

And that’s why we all have a part to play in ending the horrific IPV epidemic.

While the CLC has a dedicated online resource centre that provides detailed advice on warning signs of and risk factors for domestic violence, along with information on how people, including union representatives, can help, Smallman notes it’s important to understand our goal is not to “save” people who are experiencing violence, so to speak, or get them to leave their partner.

“Our goal is to interrupt the isolation that fuels domestic violence, to approach our members from a place of caring and concern, to make sure they are safe at work (and everyone else is safe too), and to keep them employed. To do that, we first must RECOGNIZE that someone might be experiencing or perpetrating domestic violence. We then must RESPOND with a supportive conversation. And finally, we must REFER the person to resources and supports because we are ourselves are not trained counsellors or professionals.”

CLC Human Rights Department National Director Vicky Smallman provides an eye-opening session on IPV at ONA’s recent Biennial Convention in Toronto.

“People can be kind, but still not understand what’s needed to support survivors of intimate partner violence,” explains Alice, highlighting a recent incident of physician assault that happened at her facility, which, while limited to a very small proportion of the medical profession, has been longstanding and potentially life-threatening cause of concern for nurses and health-care professionals.

“No one at work asked how that impacted me. It’s what I experienced at home on an almost daily basis. It became so normalized for me in my work and at home, I don’t even know if I realized it was happening or what to call it. But I knew enough not to speak about it over fear and embarrassment.”

While employers can take proactive steps to prevent IPV from entering the workplace and minimizing its devastating effects, Alice says she has felt “revictimized” by her employer since returning from a sick leave following that near fatal incident last year.

“Some individuals were supportive, but the system and the education just isn’t there. They don’t have the understanding or ability to provide real support for survivors of intimate partner violence. Occupational Health treated my modified work like a physical injury. No understanding of the complexity of my illness and diagnosis – just a cookie cutter plan, as if I had a musculoskeletal injury. I had to fight, argue and advocate to return to work after my short-term leave was ending or face losing my benefits, my income and my ability to provide a roof and safe place for my me and children. I strive to always ensure my standards are high, but most days I feel like I’m just surviving.”

Education

That makes the union role even more critical. To provide the support people like Alice need, the CLC offers both a one-hour primer aimed at every worker to raise general awareness of domestic violence and its workplace impact and a two-day workshop for union representatives to delve deeper, which also equips them to deliver the one-hour primer.

Learn more here.

“Perhaps our biggest piece of work is the task of building awareness among union members and training leaders and representatives, so that we can recognize and respond to domestic violence in our workplaces,” says Smallman.

Ariss concurs, emphasizing that “ONA will work tirelessly alongside the CLC and other organizations to ensure systemic change and an end to intimate partner violence once and for all. No one should have to go through what Lori, Shannan, Alice, and millions of others, have.”

“My patients, coworkers and family deserve the very best version of me,” concludes Alice. “With support from the amazing leaders at ONA, I know I can be that for everyone. But without changes, education and awareness, this epidemic will evolve, we will see higher burnout, higher absenteeism, higher mortality and higher deaths.

“I survived, my children survived, but the battle rages on.”

If you’re experiencing IPV, you’re not alone or to blame.